Andrew Jackson Smith is, without a doubt, an American hero — but for more than a hundred years, his heroism was ignored and all but completely forgotten. Heroes are not easy to find, especially in rural, small-town America. When one turns up, out of the blue, we should do everything we can to make sure we remember and honor them. Smith earned the highest military award for valor, the Medal of Honor. He was one of twenty-five Black soldiers whose bravery under fire during the American Civil War earned them this rare commendation. But, in Smith’s case, the recognition came very late, nearly sixty-nine years after his death.

For more than a century, the United States has been mired in intentional forgetting. Other nations — Germany after the Holocaust and post-Apartheid South Africa, among others — have taken steps to acknowledge and reckon with the lingering effects of the most shameful facets of their national history. The United States has not. The longer we continue our willful ignorance of America’s history of genocide, slavery, and systemic racism, the more we pour salt into our collective wounds.

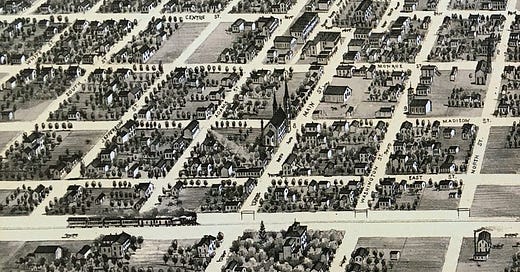

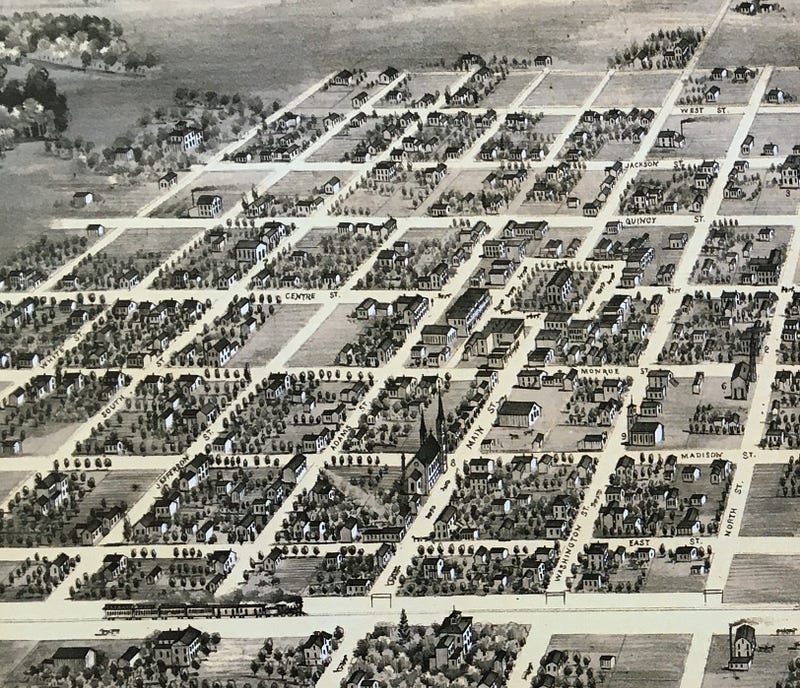

Today, in 2020, many White Americans like me are finally beginning to see what has been painfully obvious to Black Americans for so long — the depth of the injustice and shame embedded in monuments built long after the end of the Civil War to honor Confederate defenders of slavery as “heroes.” We need to find new heroes, heroes more deserving of our attention. For my hometown of Clinton, Illinois, Andrew Jackson Smith is exactly the kind of hero we need to recover, remember, and honor in the town square, in our local history museum, in our public schools. He has been forgotten for far too long.

***

In February 2020, I visited the Smithsonian’s still relatively new — dedicated by President Barack Obama in September 2016 — National Museum of African-American History and Culture and moved with the flow of a wave of school groups, families, and tourists, all of them eager for a glimpse of the wonderful and long overdue exhibits showcasing but a small fraction of the myriad contributions Black Americans have made to American greatness.

I was not able to linger in most areas of the museum, but at one point I found a relatively quiet hallway where I could take my time. The hallway contained portraits of a small sampling of African-American soldiers who had earned the highest military decoration awarded by the United States, the Medal of Honor. The Medal of Honor originated during the Civil War and twenty-five African-American soldiers and sailors earned the award during that conflict, a testament to their bravery and indicative of the significant contributions U.S. Colored Troops made to the Union victory.

The next day, I was one of a small handful of visitors to the African-American Civil War Museum, a small museum, hidden behind a construction site, dedicated to the history of U.S. Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.) and their role in the Civil War. At the museum I learned that the recruitment of Black soldiers by the Union Army began after Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, freeing slaves in rebel-held territories. In May 1863, the Bureau of Colored Troops was organized and it oversaw the formation of about 175 regiments of United States Colored Troops (U.S.C.T.).

The soldiers of the U.S.C.T. were mostly freed slaves or free Blacks, but the U.S.C.T. also included in its ranks, Native Americans, Pacific Islanders, and Asian Americans, all led by White officers. During the last two years of the Civil War, U.S.C.T. soldiers fought on the front lines and participated in the siege and occupation of many Confederate cities. By the end of the war, the U.S.C.T. comprised a tenth of all Union troops. The mortality rate for Black soldiers in the U.S.C.T. was twenty percent, much higher than the rate for White soldiers in the Union Army. And, until Frederick Douglass lobbied successfully on their behalf — Douglass had two sons in the U.S.C.T — Black soldiers in the U.S.C.T. were also paid less than their White counterparts.

***

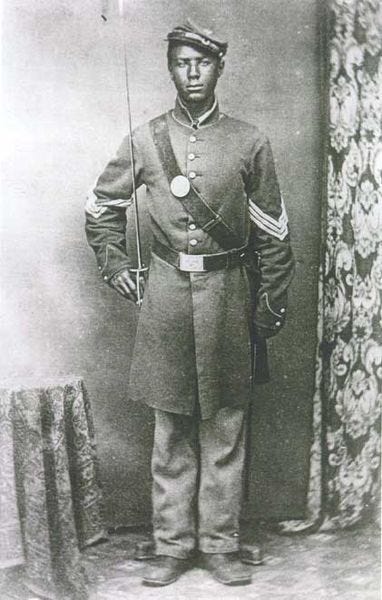

Back home in California in September 2020, I searched online for more information on Black Civil War soldiers who had earned the Medal of Honor. Looking down the list of twenty-five names, a photograph of the young Andrew Jackson Smith caught my eye.

Perhaps it was his name, or the jaunty angle of his cap, or the too-large tunic, or perhaps it was the determined look on the young soldier’s face in the photograph, but something made me choose Andrew Jackson Smith and learn more about him. When I searched for his military records, the first thing I saw was a note saying that Smith’s Medal of Honor was awarded posthumously, presented to Smith’s ninety-three-year-old daughter, in January 2001!, by President Bill Clinton, one of Clinton’s last acts before leaving office, and 137 years after Andrew Jackson Smith’s heroic actions at the Battle of Honey Hill that earned him the citation. Then I read the text of the citation.

Corporal Andrew Jackson Smith, of Clinton, Illinois, a member of the 55th Massachusetts Voluntary Infantry, distinguished himself on 30 November 1864 by saving his regimental colors, after the color bearer was killed during a bloody charge called the Battle of Honey Hill, South Carolina. In the late afternoon, as the 55th Regiment pursued enemy skirmishers and conducted a running fight, they ran into a swampy area backed by a rise where the Confederate Army awaited. The surrounding woods and thick underbrush impeded infantry movement and artillery support. The 55th and 54th regiments formed columns to advance on the enemy position in a flanking movement. As the Confederates repelled other units, the 55th and 54th regiments continued to move into flanking positions. Forced into a narrow gorge crossing a swamp in the face of the enemy position, the 55th’s Color-Sergeant was killed by an exploding shell, and Corporal Smith took the Regimental Colors from his hand and carried them through heavy grape and canister fire. Although half of the officers and a third of the enlisted men engaged in the fight were killed or wounded, Corporal Smith continued to expose himself to enemy fire by carrying the colors throughout the battle. Through his actions, the Regimental Colors of the 55th Infantry Regiment were not lost to the enemy. Corporal Andrew Jackson Smith’s extraordinary valor in the face of deadly enemy fire is in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon him, the 55th Regiment, and the United States Army. [emphasis added]

I had to read the citation twice before I would acknowledge to myself that the citation said Smith was from the town where I was born and grew up, Clinton, Illinois. I thought it must be a mistake. Perhaps there was some confusion because the citation was awarded by President Clinton. I just could not fathom how it was possible that Andrew Jackson Smith was actually from Clinton. I had previously looked carefully at the 1860 U.S. Census records for Clinton and knew there was no Black family by the name of Smith living in the town at the time.

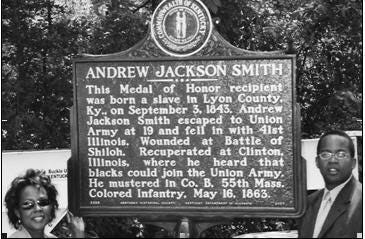

Initially, as I began to find more biographical background on Smith, I felt that my suspicions that a mistake had been made in the citation were being confirmed. Andrew Jackson Smith was born on September 13, 1843 in Lyons County, Kentucky. His mother was Susan, a slave, and his biological father was Elias (or Elijah) Smith, the White man who owned them both. At the start of the Civil War, Elias Smith joined the Confederate Army. A year later, he returned home and announced his intention to take “Andy” with him to serve as his body servant when he returned to duty. Andy and another slave ran away, walking twenty-five miles through icy rain to Smithland, Kentucky where they knew they would find an outpost of Union troops.

In Smithland, young Andy met Dr. John Warner, of Clinton, Illinois, now Major Warner of the 41st Illinois Volunteer Infantry. Warner took Andy on as his servant. By April 1862, the 41st had moved on to Tennessee where they took part in the Battle of Shiloh. In the course of repeatedly coming to the aid of Major Warner in that battle, Andrew Jackson Smith was seriously wounded. John Warner’s son, Vespasian Warner, described what happened during the Battle of Shiloh in a letter he wrote in 1917 to support Smith’s Medal of Honor application.

March 10, 1917: _Dear Sir:_Mr. Andy Smith of Grand River, Ky., having asked me to write you what I remember in relation to a wound he received at the battle of Shiloh, I will state that for some time before that battle he had been a servant of my father, who was the Major and afterwards Lieutenant Colonel in command of the 41st Illinois Volunteer Infantry, and when the battle opened, my father told Andy to keep him in sight with a canteen of water, and if he, my father, should fall, to come to him with the water. That sometime after my father’s regiment became engaged the horse on which he was mounted was wounded and my father was dismounted and turning found Andy standing close to him and giving the wounded horse to Andy, told him to take it to the rear and stay there. A short time afterwards a horse from which some Confederate had been shot, galloped out between the lines and my father rushed out, caught and mounted him. _Soon afterward this second horse was wounded and my father again dismounted and turning, found Andy standing close to him again and handing the second horse to Andy, told him to take it back and keep out of danger, and just then Andy received a gun shot wound in the head from the enemy. _The above is all I remember of the matter. Andy was certainly a brave and loyal boy. _Yours truly,_Vespasian Warner

After Smith was wounded at the Battle of Shiloh — a spent Minie ball had struck him in the head, not hard enough to pierce the skull, but sufficiently hard to knock him out, and to travel under the scalp before coming to rest at the center of his forehead — he needed surgery and time to recuperate. So did Major Warner who, at Shiloh, had contracted severe diarrhea, a chronic condition that would plague him for many years. After Shiloh, in May 1862, the two of them returned to Clinton for a long furlough.

On January 1, 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation making it possible for Andrew Jackson Smith and other Black soldiers to serve in the Union Army. In the spring, John Warner bought a train ticket to enable Smith to travel to Boston and enlist in the Massachusetts Colored Volunteers. On May 16, 1863, Smith joined Company ‘B’ of the 55th Massachusetts Volunteer Regiment and, over the next two and a half years, fought in and survived numerous military engagements, including the bloodbath of the Battle of Honey Hill, in which Smith demonstrated “extraordinary valor in the face of deadly enemy fire.”

Smith’s White commanding officer at the Battle of Honey Hill, Colonel Alfred Hartwell, was wounded early in the action and was not able to complete his report of the battle, and of Smith’s bravery, until 1870, years after the war had ended. The delay seems to have caused the records to be misplaced and ignored, including Hartwell’s recommendation that Smith be awarded the Medal of Honor. It was not until late 1916, after years of prompting from Smith, that the Army re-opened the files to consider whether or not to grant Smith the Medal of Honor.

Vespasian Warner was just a year older than Andrew Jackson Smith, so the fact that he describes Smith in his 1917 supporting letter as “a brave and loyal boy” is more than a little disconcerting. It reflects the deepening of systemic racism in America after Reconstruction. Still, Warner told the truth about Andrew Smith’s bravery in protecting his father’s life at the Battle of Shiloh.

You might think the testimony of Vespasian Warner, a former Member of Congress and from 1904 to 1909 the Teddy Roosevelt-appointed Commissioner of Pensions (equivalent to today’s Secretary of Veterans Affairs), would have counted for something in Washington, but in 1917 the President was Woodrow Wilson, a man whose fondness for D.W. Griffith’s film, Birth of a Nation, helped inspire the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan. Smith’s 1916 application was denied, ostensibly because the Army determined there was insufficient documentation of Smith’s Civil War service.

It was the persistent efforts of Andrew Jackson Smith’s descendants, including his daughter Caruth Smith Washington, born in 1907, and his grandson, Andrew Smith Bowman, with help from many others who finally, eighty-four years after the death of Andrew Jackson Smith, saw justice done with the award of the Medal of Honor. At age ninety-three, Caruth Smith Washington accepted the award on behalf of her father. Some say that before she died at the age of 104 in 2012, Caruth Smith Washington had become the last living child of an American slave.

***

I understand now why Andrew Jackson Smith’s long-overdue Medal of Honor citation says he was from Clinton, Illinois. It is not a mistake, but it is also not the whole story. Smith was living in Clinton at the time he went to Boston to enlist in the Massachusetts Colored Volunteers. As far as his military records are concerned, Clinton was his home. He also lived in Clinton for a short time after he was discharged from the Army in August 1865. But within just a few years, Smith moved to Eddyville, Kentucky, where he was able to purchase some land. In 1870, Smith was living with his wife in Lyon, Kentucky. He remained in Kentucky until his death at age eighty-eight in 1932.

Grand Rivers, Kentucky where Andrew Jackson Smith is buried and not far from where he was born, deserves the honor of claiming Smith as a native son far more than Clinton, Illinois. But the citizens of Clinton did help Smith along on his road to becoming an American hero, and there can be little doubt that Smith did, in fact, earn that status. So it was disappointing to me to learn how long it took for Smith to get the recognition he deserved and it is deeply disturbing to see how his place in the history of my hometown came so close to be completely erased.

Much more work remains to be done before the people of Clinton fully acknowledge and show pride in Andrew Jackson Smith, one of only two Medal of Honor winners in the town’s history (Pvt. John O’Dea, an Irish immigrant, was the other, for actions in Vicksburg, MS in May 1863). In 2002, the State of Kentucky put up a commemorative Historic Marker near Smith’s home in Lyon County. Smith’s grandchildren, Catherine Bowman and Andrew Smith Bowman, were there for the unveiling. My hometown, Clinton, and the State of Illinois should also remember Andrew Jackson Smith. I intend to do whatever I can to see that we do.